Ingredients

Vegetable Oils

Oils are fats refined from plant seeds, nuts, beans, or fruit. They are mechanically or chemically extracted, refined or unrefined, polyunsaturated, monounsaturated, or hydrogenated. Oils are essential in many food preparations for cold sauces, including mayonnaise and vinaigrette.

Extraction Methods

The hydraulic press method is the oldest and most natural way to extract oil. It has been used for centuries to process extra virgin olive oil and is the only method recognized as actual cold pressing.

The expeller method uses a mechanical press to extract the oils. This process generates heat from the friction of the press to about 120˚F (49˚C), but it still qualifies as cold pressing.

The cheapest way to extract oil is through chemical extraction with the help of petroleum-based solvents. This involves heating the seeds or plant fibers and adding the chemicals to dissolve and separate the oils. Considered the most efficient way of extraction because it recovers up to 99% of the plant oils, it also is the most destructive to the environment. These oils are highly refined through further processing. The majority of soybean oil on the market is processed using chemical extraction.

Cold-pressed oils are either hydraulic or expeller-pressed. The term is not regulated and, therefore, subject to different interpretations. Generally speaking, the oil temperature must never exceed 120 ˚F (49˚C) during the process, but true cold-pressed extra virgin olive oil, according to the International Olive Council, must never be higher than 86°F (30°C).

Refined & Unrefined

Unrefined oils are filtered and bottled without further processing and are considered healthier because they retain more nutrients. They have more flavor and color, some visible impurities, and are susceptible to spoiling faster. Unrefined oils have a lower smoke point; certain ones, including extra virgin olive oil, are not intended for frying.

Refined oils are heated to 450˚F (225˚C), deodorized, and bleached to remove unwanted odors and colors. This process strips out flavor and nutrients, often producing bland, neutral-tasting oil. The advantage of refined oils is that they have a longer shelf life than unrefined oils.

Hydrogenation

Hydrogen atoms convert liquid oils into solid or semi-solid fats like shortening and margarine. Hydrogenated oils are used in baking as a substitute for butter. The advantage of hydrogenation is that the oils are easier to store and resist rancidity, plus they provide texture in baked goods. However, hydrogenated oils have been found to contain trans-fatty acids that elevate bad cholesterol in humans and, therefore, should be eaten minimally.

Saturated, Monounsaturated & Polyunsaturated Oils

All fats and oils contain certain levels of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats. Animal fats, coconut, palm kernel, and palm oil have more saturated fats than mono and polyunsaturated fats. Fats lower in saturated fats are healthier for humans.

Saturated fats contain a chain of carbon atoms fully saturated with hydrogen atoms. Animal fats, such as lard, butter, cream, and cheese, usually contain a high proportion of saturated fat. Some vegetable oils high in saturated fats include coconut oil, cottonseed oil, and palm kernel oil.

Monounsaturated fats have one double-bonded, unsaturated carbon in the molecule. Monounsaturated fats are typically liquid at room temperature but semi-solid or solid when chilled. Monounsaturated oils include olive, sunflower, canola, grape seed, peanut, sesame, almond, and avocado.

Polyunsaturated fats have more than one double-bonded or unsaturated carbon molecule and are considered healthier because they contain Omega-3 and Omega-6 fats. They are liquid at room temperature and when chilled. Vegetable oils, including soybean, corn, and safflower oil, and fatty fish, such as salmon, mackerel, herring, and trout, are all high in polyunsaturated fats. Other sources include flaxseed, walnuts, and sunflower seeds.

Storing Oils

Oils will spoil with age or abuse. Keep oils appropriately sealed and store them in a cool, dark place. If the oil has a strong aroma and taste, it is rancid and should be discarded.

Olive Oil

Oil produced from olives possesses unique qualities and traditions, unlike other oils. Its roots and history date back thousands of years to areas in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. The earliest references to the use of olive oil can be found in Crete, Syria, and Egypt. Today, Spain, Italy, and Greece are the largest producers of olive oil.

The International Olive Council recognizes ten categories of olive oil based on production methods, taste, purity, and the level of oleic acid detected in the oil. Olive oil production can be dependent on factors similar to winemaking, including the climate, cultivation, and terroir where the olives are grown. Taste factors when evaluating olive oil include fruitiness, pungency, and bitterness. Good quality olive oil should have a date of harvest stamped on its label.

Extra Virgin Olive Oil is the first pressing of olives and is generally considered the highest quality and most flavorful. It is mechanically extracted without heat or chemicals. The oleic acid in the oil must not exceed 0.8 grams per 100. When harvested, extra virgin oils have a bright, fruity taste but darken and mellow with age.

Virgin Olive Oil is expressed mainly by its oleic acid level of 2 grams per 100.

Olive Oil is a blend of virgin and refined oil.

Olive Pomace Oil is one of the lowest categories of olive oil. It is produced by chemical extraction and is blended with other oils.

Culinary Preparations

Heat affects oil, and certain oils tolerate heat more than others. Refined oils usually have a higher smoke point than unrefined and minimally processed oils. Matching the oil to the type of culinary preparation is vital because oils that cannot tolerate a high smoke point become unhealthy and can taste bad. Delicate oils like extra virgin olive oil shouldn’t be used to cook with them because the heat destroys their flavor, which is a waste of money. Use extra virgin olive oil in cold preparations or as a finishing garnish for hot dishes.

Vinegar

Vinegar, a fermented product created from alcohol, was first discovered as a byproduct of winemaking, which the French called vin aigre or sour wine. When wine is exposed to oxygen, naturally occurring bacteria feed off the sugars in the alcohol, creating acetic acid or vinegar as we know it. Vinegar can be made from any fruit or grain that contains sugar. The most common varieties are prepared from grapes, apples, and rice.

Production Methods

Orleans Method

This traditional method was developed and named for the region in France where it was first invented. Alcohol is placed in wooden barrels with a starter vinegar, also known as the mother, an acetobacter film found on the surface of naturally fermented vinegar. The barrels have air holes to allow circulation and are left to sit for several months at a room temperature of approximately 85°F (29°C).

Submerged Fermentation

Alcohol is placed in stainless steel tanks called acetators and is pumped with air while a temperature between 80 -100°F (6-38°C) is maintained. The vinegar is filtered and diluted to the proper acidity level. This method creates wine vinegar, which yields results in 24-48 hours.

Production Notes

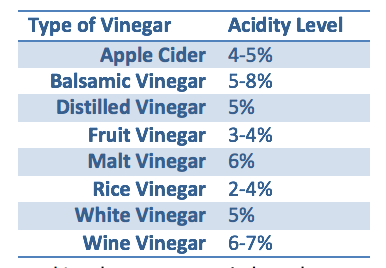

Vinegar's acidity levels will vary during production but are diluted to around 5% on average to as high as 8%. Vinegar is often pasteurized and filtered to remove impurities. Vinegar naturally has a “mother” that is a byproduct of vinegar production. This harmless sediment forms in the bottle and is often removed by filtering.

Trickling or Generator Method

Alcohol is poured over layers of wood or fibrous shavings, onto which acetobacteria are introduced. The trickling method allows the bacteria to circulate freely with the alcohol, creating vinegar in a few days.

Submerged Fermentation

Alcohol is placed in stainless steel tanks called acetators and is pumped with air while a temperature between 80 -100°F/6-38°C is maintained. The vinegar is filtered and diluted to the proper acidity level. This method creates wine vinegar, which yields results in 24-48 hours.

Types of Vinegar

Wine Vinegar

Balsamic, white, red, champagne, and sherry wine vinegar are the most common on the market.

Balsamic Vinegar

Traditional balsamic vinegar is produced from the white Trebbiano and Lambrusco grapes in barrels, similar to wine production. This process, dating back to the Middle Ages, is native to Italy's Modena and Reggio Emilio regions. Grape juice is reduced to a must and then transferred through seven different barrels during the 12-25-year aging process. Some balsamic vinegar is aged as long as 100 years and becomes thick with a syrup consistency. Imitation balsamic vinegars that mimic the primary flavors are produced today, but authentic balsamic vinegar is a protected designation in Italy. Its sweet, caramel acidic taste pairs well with salads, grilled meats, and fresh fruits.

Sherry Vinegar

It is known as Vinagre de Jerez in Spain and is produced within what is known as the sherry triangle near the city of Jerez. The area is a designated Denominación de Origen, a regulatory classification for sherry wine and vinegar in that region. Sherry vinegar must be aged in American Oak for a minimum of 6 months, can only be produced in this region, and has an acidity level of 7%. Vinagre de Jerez Reserva is aged a minimum of 2 years, and Vinagre de Jerez Gran Reserva is aged a minimum of 10 years. Different grapes are used depending on the desired style, including the Palomino, Pedro Ximénez, or Moscatel grapes.

Apple Cider

Apple cider or apple must are made into cider vinegar using the same production method as wine vinegar.

Distilled Vinegar

Made from distilled grains and used for many basic food preparations, including pickling. It is also used as a cleaning solution and effectively kills mold and bacteria.

Fruit Vinegar

Raspberries, blueberries, strawberries, and other fruits can be used to make vinegar. These vinegars are usually either made from fruit wines or are infusions of fruits added to red or white wine vinegar as a base.

Other varieties that can be found on the market include cranberry, pear, pomegranate, and peach.

Malt Vinegar

Produced from ale made with malted barley or corn, this vinegar is light brown.

Rice Vinegar

Popular in Asian cuisine, rice vinegar is produced in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. The vinegar is mildly acidic and sometimes sweetened or seasoned for use in sushi and sashimi. The most popular type is Japanese white or pale rice vinegar, which can be found in seasoned and sweetened varieties. Chinese versions include an amber-colored, black-colored, and red variety.

Infused Vinegar

Infused vinegar can be made using methods similar to infused oils. The simplest method is to add herbs or spices to vinegar and let it sit for some time to infuse the flavor. The vinegar can be heated first to help speed up the infusion process.

Nuts

Nuts are seeds with hard shells that are reproductive units for various trees. They are high in protein, carbohydrates, and oil and provide many nutritional benefits. Nuts are processed in the shell or are shelled and sold whole, sliced, slivered, and chopped. They are also refined into oils, ground into flour, or processed into butter.

Culinary Uses

Nuts add texture and flavor accents to various sweet and savory dishes.

Cooking

Toasting nuts will bring out their flavors and textures. Toast dry or toss with salt and neutral oil, spread out on a sheet pan, and place in a medium oven to crisp the texture. Nuts can also be sautéed to crisp and brown them, but this process can lead to uneven browning. Nuts can be pureed to thicken soups, sauces, and stews.

Storage

Because of their fat content, nuts are perishable and susceptible to spoilage. Nuts that turn rancid have a distinct odor and taste and should be discarded. Chopped or ground nuts spoil faster than whole or in-the-shell nuts. Store nuts in an airtight container. Refrigeration or freezing will extend their shelf life but can result in them taking on a mealy texture. Toast nuts will crisp them up and return their texture.

One month at room temperature

Six months under refrigeration

One year in the freezer

Nut Allergies

Hypersensitivity to certain foods can lead to severe physical reactions. People with food allergies may be sensitive to more than one type of nut. Raw nuts may cause a more severe reaction than refined oils. The severity of the reaction varies from person to person, and repeated exposure can increase sensitization. The United States Food and Drug Administration requires packaged foods containing tree nuts and peanuts to list the specific ingredients on the label. In foodservice operations it is always a good policy to inform the staff of common food allergens in menu items and to make customers aware of any foods containing potential allergens.

Seeds

Grains, nuts, and legumes are all types of seeds. Seeds are reproductive units of plants. Grains and nuts all have an outer husk and a protective shell known as bran with a food source called a germ. Because the germ and bran are susceptible to disease and spoilage they are often processed to remove the outer layers and provide long and stable shelf life. This produces are more refined product but results in the loss of important nutrients in the bran and germ. Typical grains like rice are often fortified with added vitamins or nutrients to make up for this loss.

Gelatin & Agar

Gelatin

Gelatin is a rendered form of collagen used in many commercial products including candies, marshmallows, ice cream, yogurt, mousses and other sweetened gelatin desserts. Made from meat by-products including pork skin, beef hides, cartilaginous meat cuts, and bones, gelatin is extracted by heating with water and then filtered, sterilized and dried. It is further processed into powdered, granulated or sheets or leaf forms.

Gelatin Types

Powdered or granulated gelatin is commonly used in North America. Leaf or sheet gelatin is found in Europe and other parts of the world but is increasingly being found in North America as well. Leaf gelatin is considered to be superior in clarity. Both granulated and sheet gelatin can be used interchangeably in recipes but some adjustment may need to be made depending on the strength of the gelatin.

Gelatin strength is expressed by a Bloom Strength number and commercial types vary from low Bloom (<150), medium Bloom (150 - 220) to high Bloom (> 220) types. The higher the number the more thickening power it will have. Leaf gelatin manufacturers compensate for the Bloom Strength by adjusting the size and weight of the sheets so that they can be used interchangeably in recipes.

Example: a 200 strength sheet gelatin will weight .06 oz. /1.7 g and a 130 will weigh .12 oz. /3.3g.

Working with Gelatin

Gelatin must bloom or soften in soaking in a quantity of cold water before heating. For leaf gelatin submerge it completely in the water and allow it to soften. Drain the liquid and gently squeeze out the excess moisture. For granulated gelatin use approximately 5 times the volume of water as gelatin and lightly sprinkle over the water allowing it to absorb and swell. Once the gelatin has been properly bloomed it can be added to hot liquids for melting.

Gelatin and Liquids

Almost any type of liquid can be used to jell but fresh tropical fruit juices, including papaya, kiwi, mango, and pineapple contain an enzyme called bromelin that will break down the gelatin unless it is first heated and pasteurized. Salts, acids, and alcohol can also affect gelatin's ability to thicken.

Gelatin Alternatives

Plant based alternatives are used as a substitute for gelatin in many products today and has become increasingly popular in the modern professional kitchen. It is also an alternative for vegetarians or those with religious dietary restrictions. These thickeners are derived from seaweed or fruits including agar agar, guar gum, xanthan gum, pectin and kudzu.

Gelatin Tips

The melting point of gelatin is approximately 99˚F/37˚C.

Gelatin relies on a Bloom Strength number that determines its thickening power

Experimentation may be required to find a gelatin that works correctly for particular culinary applications

Do not boil gelatin because it will lose some of its thickening power.

Freezing products results in a loss in clarity and texture

When dissolving gelatin in liquids stir gently to avoid air bubbles

Sheet gelatin is considered to be clearer than granulated gelatin

Gelatin must be bloomed or rehydrated in water before using

Chill gelatin mixtures for 8-24 hours before using

One retail-size envelope of powdered gelatin = ¼ oz. /7 g = 2 ¼ tsp.

AGAR

Derived from red algae seaweed, agar agar (or agar for short) has been used for over 350 years as a thickening agent predominantly in Asia. It is used in the manufacturing of candies, desserts and ice creams. Agar has become popular in recent years because it is refined from a plant source and is a suitable vegetarian substitute for gelatin. Agar has no taste, odor, or color. It sets more firmly than gelatin and unlike gelatin holds at room temperature.

Agar is a carbohydrate that comes from the cell walls of seaweed. The seaweed is freeze-dried and dehydrated, then processed into various forms.

Properties

Agar will set in liquids at 0.5-2.0% ratio.

Agar must be dissolved in cold water and simmered at 212°F/100°C to achieve its proper setting consistency.

Once cooked, gel formation takes place at temperatures between 90-110°F/32- 43°C.

When the gel is set agar retains its firmness to temperatures as high as 185°F/ 85°C), unlike gelatin which melts at 99°F /37°C.

Gel Texture

Agar gel texture is more brittle than gelatin but the addition of sugar improves both its strength and elasticity.

Acidic Foods

Acidity in vinegars and citrus fruits affects the thickening power of agar. Strawberries and citrus may require a higher agar to liquid ratio. Tropical fruits including kiwi, pineapple, fresh figs, paw paws, papaya, mango and peaches contain enzymes that break down the gelling ability of the agar. Precooking the fruits helps to resolve some of the problem but recipes should be tested when substituting agar for gelatin or other types of thickeners.