Meat & Poultry Fabrication

The extent of meat cutting and fabrication performed in professional kitchens today depends on the philosophy and goals of the operation. Some restaurants, because of the consistency and simplicity, prefer to purchase portion cuts. On the opposite end of the spectrum, some chefs today are adopting whole animal utilization and prefer purchasing carcasses or sides of meats to use in various menu applications. The success of a meat cutting program depends on quality control, food cost control, and product utilization. It requires a knowledgeable person skilled at accurately cutting meats, poultry, fish, and shellfish, plus cooks dedicated to using not just the prime cuts but under-utilized cuts, trim, and bone for other culinary applications.

Meat Fabrication

Butchering is a term commonly used for the process of slaughtering and preparing meat for retail or wholesale use. Meat cutting, or fabrication, is the process of cutting, boning, and portioning large cuts of meat to menu specifications. Becoming proficient at fabricating whole carcasses or primal meat cuts takes practice often through an apprenticeship under a master meat cutter.

Dressed carcasses are processed whole, split into sides, or cut into quarters (fore quarter and hind quarter). More often carcasses are fabricated into primal cuts of meat. These are large cuts based on the muscle and bone structure of the animal. From there the meat is further divided into sub primal cuts that are often vacuum sealed and boxed fresh or frozen (the origin of the term “boxed meats”) or the meats are processed further into portion cuts as needed.

Seven Major Bones

Skeletal and Muscle Structure

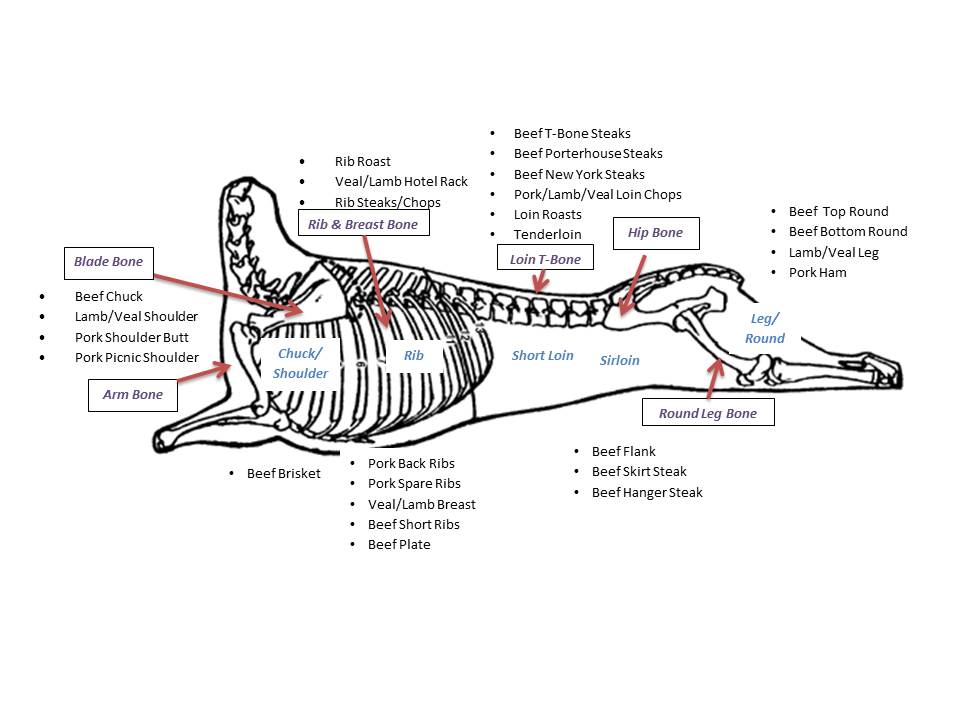

There are seven major bones in a skeleton that aid in meat identification and fabrication. Each of these seven bones are found in relation to one of the major muscles in the carcass (see skeletal meat chart).

Primal Cuts

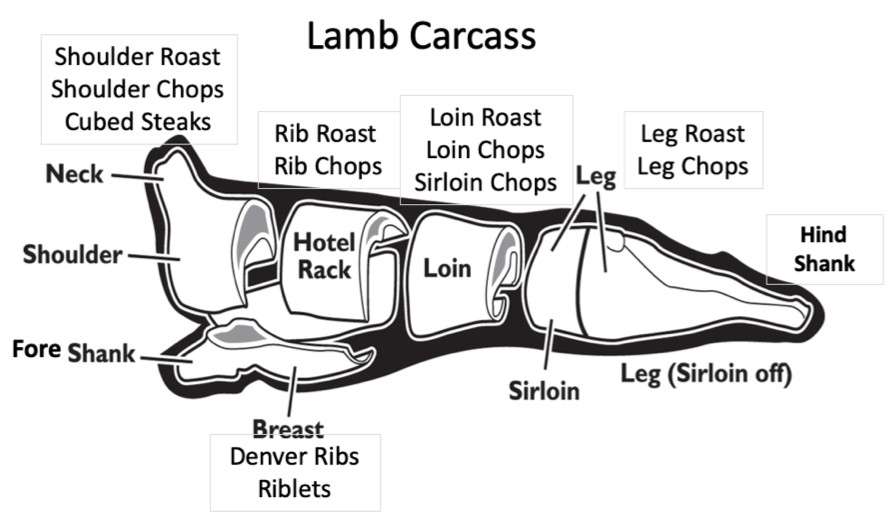

There are four major primal cuts, the shoulder, rib, loin, and leg, found on all animal carcasses, but depending on the species there are some differences in naming and fabricating these cuts. For example, a beef chuck is the same cut as a lamb shoulder or pork shoulder butt. A beef round is the same as a veal leg and a pork ham.

Location of the 7 Major Bones on a Beef Carcass

Sub-Primal and Portion Cuts Derived from the Primal Cuts

Learning the appearance and formation of major cuts along with the basic structure helps in fabricating as well as cooking. See specific meat charts on beef, veal, pork, and lamb for the names and locations of primal, sub primal, and portion cuts.

There are several minor primal cuts found on each type of carcass which are usually fabricated differently depending on the animal and its size. For example, on a beef carcass the brisket, plate, and flank are separated into three distinct cuts, but on a veal carcass it is kept whole as a bone-in veal breast.

Lamb shanks and pork hocks (or shanks) are often cooked and served whole. Veal and beef shanks are usually cross-cut for braises or soups.

Pork carcass breakdown is notably different from beef, veal, and lamb. Whereas beef, veal and lamb split the rib and loin muscles between the 12th and 13th rib, pork carcass fabrication leaves this muscle intact and names it simply the loin. Pork back ribs are marketed for barbecuing. The pork belly is a much more prominent cut producing bacon and spare ribs. The pork shoulder is split into two cuts; the shoulder butt and the picnic shoulder. The jowl produces a type of bacon, and the excessive fat often found along the backside of the animal is used as fatback or rendered for lard. The leg, known as the ham, is often cured and sometimes smoked.

Fabrication Differences Based on Size

Size matters when fabricating meats. A beef carcass weighing in at 600 Lb./275 K is about 33% larger than a veal carcass at 400 Lb./180 K. A pork carcass weighing approximately 270 Lb./125 K. is about 33% smaller than a veal carcass. A lamb carcass weighing about 65 Lb./30 Kg. is about one-fourth the size of a pork carcass and one-tenth the size of a beef carcass. The yield on the same muscle from different species can be dramatic. A steer tenderloin can weigh in excess of 6 Lb./2.7 K, compared to a veal tenderloin at about 2 lb./900 g, and a pork loin at about 1 lb./500 g or a lamb tenderloin at a couple of ounces. Some viable cuts on a beef carcass such as a hanger steak or flank steak are not marketable on a lamb or pork carcass given their small size.

Portion Cuts

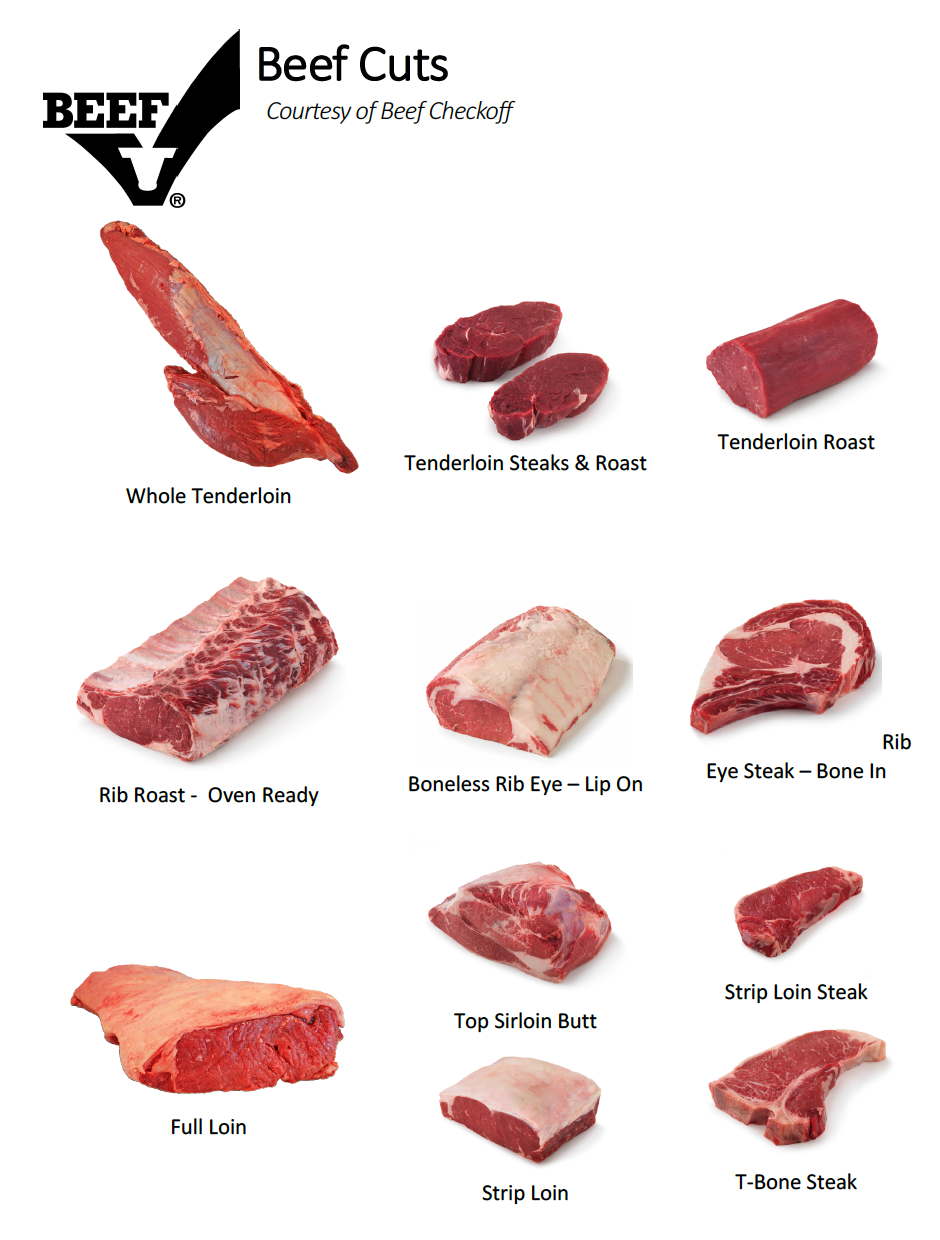

A beef full loin is an example of a primal cut. From the beef loin three major sub primal cuts are produced; the strip loin, the sirloin, and the tenderloin. A strip loin will yield New York strip steaks and if left on the bone can be portion cut into T-Bone and Porterhouse steaks. The tenderloin will yield filets, medallions, and tournedos. The sirloin yields top sirloin and beef culotte steaks. Each muscle eventually is portion cut whether raw, or as in the example of a roast, after cooking.

Start with a clean station and practice high standards of sanitation when cutting meats. Keep the product cold, and if needed place it on a pan of ice. Some operations will have temperature controlled rooms to keep the meats cold. It’s also important to have the right tools that are properly sharpened and a honing steel handy.

Portion Control

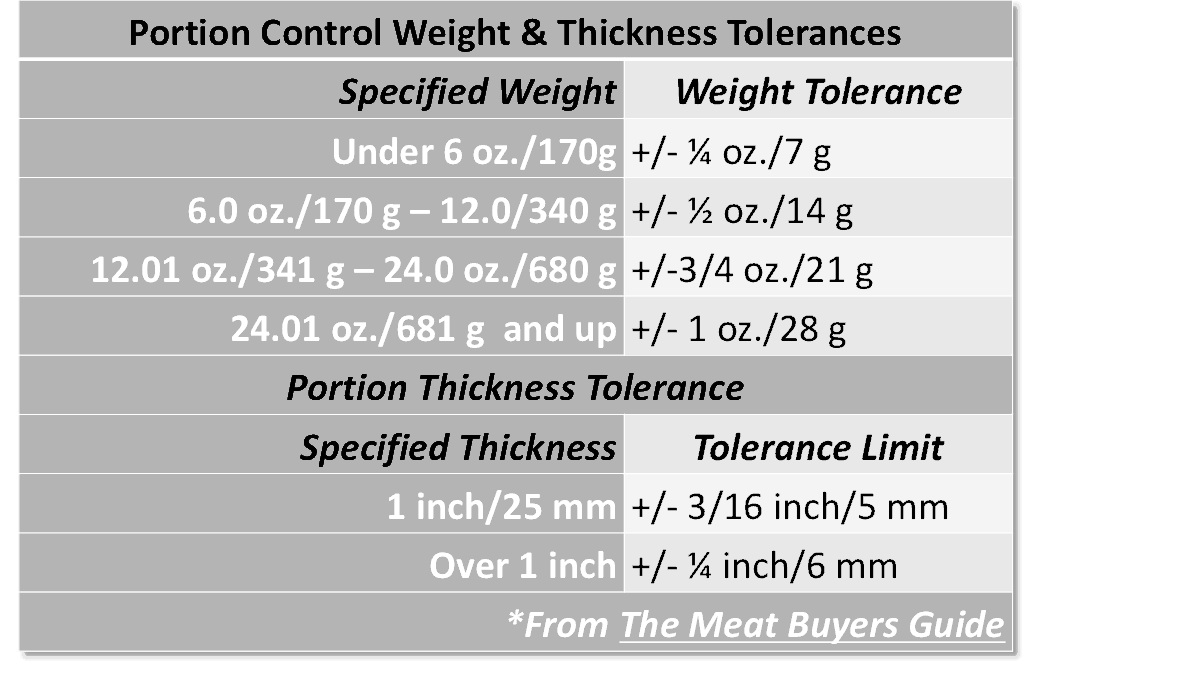

Meats are fabricated or ordered according to the specifications of an operation based on portion size usually by weight and also at times based on thickness. These guidelines ensure uniformity in appearance and purchasing costs. Weight tolerance also helps to achieve consistency in quality from the perspective of customer satisfaction. The chart shows the generally accepted weight and thickness tolerance range according to The Meat Buyers Guide.

Cutting Direction

Although whole muscles are fabricated without regard to the grain of the meat, portion cuts follow the general rule of cutting across the grain of the meat. This produces short fibers of meat that when served are easy to cut and chew.

While some cuts, like the loin and tenderloin, consist of whole muscles that are portioned by cutting across the grain, shoulder and leg cuts are made up of many muscles with varying degrees of tenderness running in different directions and making it more of a challenge to portion. For these cuts some muscles can be seamed out while others are too small and are used for braises, as stews, or for grinding.

Bone-In or Boneless

Cross-Cut Veal Shanks

Some cuts of meat, including T-Bone steaks, pork back ribs, rack of lamb, and shanks are fabricated bone-in for appearance and flavor. Bone-in meat will have more intense flavor upon cooking versus the boned variety. Today there is a preference in the United States for boneless meats that are easy to eat without the need to separaate the meat from the bone.

Connective Tissue

Connective tissue, found throughout the carcass in the form of elastin and collagen holds the muscle fibers together in bundles and also binds them to the skeletal structure. Elastin is tough and elastic, as the name implies. It does not break down in the cooking process and therefore it is best removed. Collagen when heated melts and creates gelatin and is often left on the muscle for flavor and texture.

Fat

Cover fat and intramuscular fat in the form of marbling provides flavor and juiciness. When the marbling in meat muscles melts during the cooking process it provides flavor and juiciness. Cover fat on meat roasts baste the meat naturally while cooking when roasted fat side up. Removing cover fat or seam fat is necessary at times but because it adds flavor care should be taken not to remove too much.