The Allure of Japanese Cutlery

Morimoto Cutlery Sakai Knives

In ancient Japan, it was said that the samurai sword was an extension of a warrior’s soul. The same could be said for a chef's knife because it is the most personal of any tool in the kitchen. For many years the Western-style chef knife was the standard for most cooks but in recent times Japanese knives have become popular too. Here’s a little background on the history of Japanese knives, the differences between their European and American counterparts, and how to select and maintain them.

Japanese cutlery is rooted in the samurai sword-making tradition dating back over 1200 years when the shogunate ruled the country and samurai soldiers enforced the laws of the land. When the shogunate lost its power in 1868 and the Meiji Restoration period began, efforts were made to modernize Japan and the samurai class started to decline in influence. The demand for swords began to shrink and manufacturers turned their efforts to knife making. Sakai City, once the capital of samurai sword making dating back to the 1400s, is today a major manufacturing region for cutlery where traditional sashimi knives, like the Yanigabi, with a long thin blade for slicing sashimi originated. Seki City is considered the home of modern Japanese cutlery-producing western styles knives like the Usuba, a blunt-tipped knife for dicing and slicing vegetables popular with American chefs.

Japanese knives carry a different aesthetic than their Western counterparts. Where a German-made knife is heavier with a thicker spine, a Japanese knife will have a much lighter profile and thinner blade. Japanese knives are also sharper too because the metals have a higher hardness rating which helps to maintain their edge. Until recently Western-style chef knives were manufactured with a bolster (see photo), a thick collar between the heel of the blade and the handle, although today most Western knife manufacturers produce models without the bolster too.

Types of Japanese Knives

Common knives in the Western style include a chef knife, paring knife, boning or filleting knife, slicer, and a cleaver. A gyuto is the Japanese equivalent of a chef knife (see photo). The santoku, an all-purpose knife that was developed after Japan transitioned from a vegetarian diet to eating more fish and meat, is also used similarly to a chef knife. The deba is a butcher’s knife for cutting fish, while a yanigiba is used as a filleting knife for slicing sashimi. A usuba is a vegetable knife and a petty can be compared to a paring knife.

Types of Metals

Carbon steel, made from iron and other elements including carbon and manganese, is traditionally used to forge Japanese knives. It holds an edge very well but rusts and discolors easily. Stainless steel, essentially carbon steel with the addition of chromium, tungsten, and vanadium, resists rusting and is common today in most kitchen cutlery.

Formulas for producing steel will have different levels of carbon making them harder or softer on the Rockwell Scale (HRC). The Rockwell scale is the standard for judging the hardness of a knife blade and its ability to hold a sharp edge. Most Western-Style forged knives are between 56-58 HRC while Japanese knives are often 60 HRC or above. Harder steel holds a better edge but is also more brittle and can crack or chip easier than softer metals.

There are various types of steel for example White Steel, Blue Steel (60-65 HRC), Powdered Steel (63-65 HRC), VG1(58-60 HRC), and VG10 (60-61 HRC). They are essentially recipes of different combinations of metals used by manufacturers to make their knives. Damascus Steel refers to a lost method of forging two or more types of metals to create a wavy pattern on the blade. Some methods use acids to produce an etched effect.

Kirin Hamono Chef’s Knife Featuring 69 layers of Stainless Steel with a Powdered Steel Hagane Core

Japanese Knife Forging

Hattori Gyuto

There are over 20 steps to making a Japanese knife. Forging techniques, forging temperatures, and heat treatment methods during manufacturing affect the overall quality, hardness, and appearance. The process begins by combining soft iron with steel that is heated and forged together. It is hammered and shaped creating the rough outline of the blade and the tang. The knife is then cooled and ground to create a flat surface while being hammered into shape, which also strengthens the metals. The knife is then heated to 780-830° F and quenched in water to create further hardness. It is heated again to 150-190° F and air-cooled to make it resistant to nicks. Sharpening the blade begins with a coarse flat grindstone and then it is buffed and polished. The finishing steps include whetstone sharpening and attaching the handle. Some of the best Japanese knife manufacturers include Hattori, Misono, Mizuno Tanrenjo, Sukenari, and Mr. Itou. Prices for Japanese Knives can range from $70-80 up to as much as $20,000 for custom made but the popular price range is usually between $100-300.

Blade Types

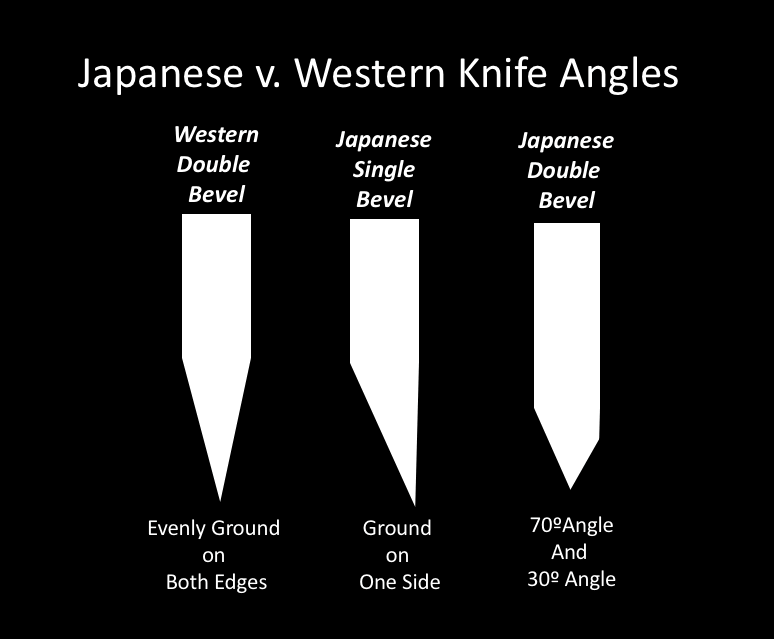

Western knives use a double bevel edge which is evenly ground on both sides of the blade. Japanese knives are either single bevel, meaning they are ground to an angle only on one side or double bevel but with an uneven angle (see diagram).

Knife Sharpening

Most higher-end Japanese knives can be sharpened to a finer edge because of their harder steel. While Western knives are generally sharpened to a 20° angle on each side (for a total of 40°), Japanese knives are sharpened to about a 15° angle (for a total of 30°). Of course, sharpening will vary too based on whether the knife is a single or double bevel. For beginners when learning the sharpening process, placing 2 coins on the stone and resting the spine on the coins will give you a feel for the angle. Every knife is different though and so getting a feel for where the edge is will help to maintain an evenly sharp edge.

Professional knife sharpeners use an electric belt or wheel sharpener to hone an edge while chefs use Whetstones when hand sharpening their knives. An oiled tri-stone sharpener will have a coarse-sided stone of about 200 grit, a medium stone, and a finishing stone with anywhere from 350 to 3000 grit (the lower the grit number the coarser the stone, the higher the grit the smoother it is.). Knives that are very dull will use a coarse grit to start and then graduate to a smooth grit finish.

Japanese whetstones (sometimes called water stones) use a much finer grit, starting at 1000 and finishing at 6000-8000 grit, which is soaked in water (instead of oil), for about 20-30 minutes before sharpening. Water is applied to the stone regularly to keep it moist and to create grit that helps refine the edge during sharpening. With frequent use, water stones become concave and need to be flattened before sharpening. After soaking the stone, sand it down with a stone fixer (see photo) to even it out.

When sharpening any knife, consider the blade as an extension of your arm. Find the correct bevel angle of the edge, and always apply consistent pressure along the blade so that the edge is sharpened evenly from the tip to the handle. Draw the blade back and forth repeatedly, always applying more pressure during the strokes when the edge is drawn away from the stone.

Sharpen one side of the blade until you create a burr along the opposite edge, which is the edge folding over. Check for the burr by running your thumb across the edge of the opposite side you are sharpening. Once you can feel the burr, flip the blade and begin sharpening the other side of the knife.