Meat - Farm-to-Table

Meat and poultry are a major part of the American diet, and because of their expense, they are a large percentage of the budget in a foodservice operation. Understanding how to purchase, store, process, and cook these foods will help you maximize their quality and yield while minimizing their expense. Here are the basics on animal proteins, including how they are raised and harvested, inspected and processed, their composition and structure, and ways to fabricate them.

Meats prepared in most foodservice operations include commercially farmed and processed beef, pork, veal, and lamb. Game items such as venison, boar, bison, and rabbit are prepared and consumed to a lesser extent, often in more upscale operations. Meats also include the internal organs of the animals, called variety meats or offal, including liver, kidneys, heart, sweetbreads, and tongue.

Meat

The majority of animals raised for food are conventionally farmed in confined animal feeding operations (CAFO) to maximize their growth potential. Beef cattle are pastured on grass for about six months and are finished in a feedlot on a diet of corn, soybeans, and other grains to rapidly build muscle weight. Beef cattle take 14-16 months from pasture to processing at a market weight of about 1,200 pounds. Veal is the male offspring meat procured from beef dairy cattle that are bred to about nine months of age with a maximum live weight of 750 lb./340 kg. Veal calves are raised in hutches, stalls, or various types of group housing and fed a formulated diet of milk-based proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Pigs are typically raised in confined group housing, with as many as 2500 hogs in a building. They are fed a diet of corn and soybean. Pigs grow to an average weight of about 270 lb./120 kg and are slaughtered at approximately six months of age. Sheep are grass-fed in pastures or barn-raised on a diet of hay or wheat and finished on grains similar to beef. American lambs are typically slaughtered at 12-14 months with an average weight of 135 pounds

Meat and Poultry Labeling

Certified Organic

Livestock must be raised on a “certified organic” farm or ranch according to United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) standards and fed only certified organic feed.

Naturally Raised

Animals are raised without growth hormones or antibiotics, and never fed animal by-products

No Antibiotics

Animals never receive antibiotics

No Hormones

Livestock never received growth hormones (Federal law prohibits the use of hormones in pork, lamb and poultry).

Grass Fed Meats

According to the USDA, beef, bison, lamb and goats can be labeled as grass fed if they forage on a diet of grass, legumes, and grain crops in their vegetative, ore-grain state. They must be allowed pasture to roam.

Free Range

The USDA designates that free range poultry be allowed access to the outdoors as alternatives to battery cages and barn floors but there is no requirement that they be given access to pasture. Free-range chicken eggs, however, have no legal definition in the United States. There is no legal standard for free range meats.

Cage Free

Cage free usually refers to egg production and means that the animals have not been penned in battery cages but are allowed access to move around whether either on a barn floor or outdoors.

Most animals raised for food in the United States are allowed to be administered antibiotics to maintain their health, and except for veal, are allowed to be given growth hormones to promote weight gain. Although the normal diet for cattle and sheep is grass-based, the addition of corn and other grains helps them to quickly gain weight. Grain-based diets pose health risks to ruminant animals but it does help them to rapidly gain weight. In recent years alternative farming methods, traditional processes that predate the high-production farming models in use today, have seen a resurgence because they allow animals access to the outdoors, and the ability to graze on a natural diet of grass. Alternative or sustainable farming methods include organic and grass-fed methods.

Heritage Breeds

Heritage breeds are distinct livestock that can be traced to the period before industrial farming and are considered endangered. Heritage livestock are generally heartier breeds that mature more slowly and are raised more naturally. Wagyu beef, from Kobe, Japan, and Berkshire pork are two examples. However, the term “heritage” does not necessarily mean they are pastured using humane farming methods, or that their meat is superior tasting. Heritage breeds help keep diversity within livestock species and help maintain the earth’s bio-diversity.

Chianini

Waygu

Texas Longhorn

Highland

Rhode Island Red

Plymouth Rock Chicken

Commercial Meat Processing

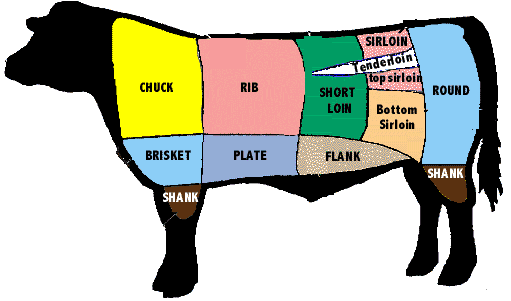

Meat processing today has become a highly automated and efficient operation. Animals are butchered and processed in one facility. Meat is fabricated into large primal cuts based on the muscle and bone structure of the animal, and further divided into sub primal cuts, portion cuts, or ground meats. A beef full loin is an example of a primal cut. From the beef loin three major sub primal cuts are produced: the short loin, the sirloin, and the tenderloin. A bone-in short loin can be portion cut into T-Bone and Porterhouse steaks (and if boned becomes a strip loin producing New York strip steaks). The tenderloin will yield filet mignon, medallions, and tournedos. The sirloin yields top sirloin and beef culotte steaks. Each muscle eventually is portion cut, whether raw or after it is cooked. Meats are vacuum-packaged for preservation, and boxed for ease in storage and shipping. Animals are bred for meat consumption but byproducts produced include leather, soaps, candles (tallow), and adhesives. There is less than a 50% yield from live weight to processed weight.

Meat Inspection and Grading

All meats sold for human consumption are inspected for wholesomeness through the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), or similar in-state agencies, to ensure they are slaughtered and processed according to safe and sanitary standards. A round stamp located on the animal’s carcass, or affixed to packages of processed meats, indicates these products are safe to consume. Exotic farmed-raised species (buffalo, rabbit, reindeer, elk, deer, and antelope) are inspected under a volunteer program. Wild game is not permitted to be sold commercially.

Premium grade meats are optionally evaluated and ranked according to quality and yield. Quality grading is based on a visual inspection of the animal’s muscle conformation and intramuscular fat, known as marbling, distributed throughout the muscles of meat. Higher quality meats have an abundant amount of marbling that contributes juiciness and flavor to their taste. The most in-demand grades for beef are prime, choice, and select, while similar grades for lamb and veal are prime and choice.

USDA grades for pork reflect only two levels of quality for pork which are acceptable and utility grades. Pork sold as utility is used in processed foods and not available to the retail market. Meats of inferior quality are usually not evaluated below these grades because it does not add to their value.

Beef and lamb are also graded for yield based on the amount of lean meat to fat and bone. The yield grade system uses a scale of 1 to 5 with the number “1” having the highest yield and number “5” having the lowest yield. Since cover fat and marbling are important quality factors in prime and choice meats, the yields from these grades will usually be a “2” or “3” yield. Beef and lamb are graded for both quality and yield.

Some trade groups or meat packers have established their own private label meat grading programs as a marketing tool to differentiate their products from other meat processors. The characteristics go beyond the requirements for official USDA grades. Some programs require USDA approval while others do not, and include among many others, programs for certified beef, grass-fed cattle, and free-range veal. These products should be evaluated on their quality, yield, and consistency in relation to the needs of each foodservice operation.

Meat Storage and Aging

Meats are considered TCS (temperature control for safety) foods and should be refrigerated between 32-36F/0-2C or frozen below these temperatures to limit food pathogen growth and maximize the shelf life of the food.

Freshly slaughtered meat, also known as green meat, stiffens from the effects of rigor mortis and must be aged to soften muscle tissue. For some animals this can be as short as a few hours and for others it can take days. By aging meats under a controlled environment, enzymes in the meat tissue break down the muscles developing tenderness and flavor during the process. Aging is done either by vacuum packaging the meats and chilling under refrigeration, a process known as wet aging, or the product is dry aged, through exposure to a refrigerated, air-circulated, and moisture-controlled environment. Dry aging produces a “meatier” flavor but results in greater moisture loss and product shrinkage. Large cuts of meat are stored under refrigeration and exposed to air circulation which limits humidity. Because of the potential for mold growth, ultraviolet lights are often used to reduce bacteria. Aging is done from 7-35 days or more, with 14 days providing optimal tenderness, flavor, and juiciness. Dry-aged meats lose 10% or more of their weight through moisture loss, and because of extended storage costs and product shrinkage are more expensive than wet aged meats.

Wet aging results in less moisture loss and better product yield. Vacuum packaging also helps to protect the meat from bacterial growth and extends the shelf life of the food. It’s important to note that meats in vacuum packaging may have a musty smell when first opened but this odor should quickly dissipate. Remember too that aged meat, whether wet or dry, should never smell spoiled.

Dry Aged Beef

Meat Composition

An animal carcass, when processed, consists of bones, muscle, and fat. Meat is muscle tissue composed of approximately 21% protein, 73% water, 5% fat, and 1% minerals. Animal proteins are nutrient dense building blocks that provide energy and keep the body functioning well. Meats are composed mostly of water so it’s important to remember that the more meats are cooked, the less yield they will produce. Fats are essential in the diet because they store nutrients and provide energy, although vegetable fats are generally considered better for you than animal fats which contain higher amounts of cholesterol. Meats also contain small amounts of nutrients that are beneficial to the human diet.

Meat consists of proteins in the form of muscle fibers or strands that are bundled and held together with connective tissue, called tendons, which harness the muscles together in bundles to the skeleton. Fat is dispersed in and around the muscle fibers. Connective tissue, a form of protein, is divided into elastin and collagen. Elastin is found in ligaments that connect the bones to the joints. Elastin, also called silver skin, does not break down in the cooking process and is usually removed mechanically in the fabrication process. Collagen is a type of protein that melts into gelatin when cooked, contributing flavor and mouth feel to meats. The muscle fiber structure is composed of smaller bundles called fascicles that are wrapped in collagen. The fascicles appear as grains in the muscle and there is a direct correlation between the fascicle grain size and tenderness. Meats from lightly exercised muscles are fine grained, feel smoother in texture, and are relatively tender. While those from muscles that are exercised more will appear larger, have a coarser texture, and a tougher consistency. A dramatic difference can be observed when comparing the fine fascicles of beef tenderloin to coarser ones from a beef brisket.

Meat Identification

Animals raised for food have the same basic skeletal and muscle structure. Although beef, pork, lamb, and veal vary in size and weight, primal, sub primal, and portion cuts can easily be identified once a connection is made between the muscle formation, the bone structure, and their general shape, size, and contour. The ability for a chef to easily identify meats aids in fabricating and ultimately determining the best cooking methods for a particular cut.

Institutional Meat Purchasing Specifications

Because of regional and international differences in meat identification, the National Association of Meat Purveyors (NAMP) developed The Meat Buyers Guide as a standardized approach to meat cutting and purchasing. The Institutional Meat Purchasing Specifications (IMPS) standardizes the cutting and trimming of meat cuts in the United States and provides a numbering system to streamline the order specification process. All beef cuts are numbered between 100 -199. As an example, a beef carcass is number 100 and a side of beef is 101. A beef primal rib is number 103. A beef rib, roast ready, is #109. Portion cuts begin with the number 1000. A beef rib steak is #1103. Color photos of the various cuts are provided. The Meat Buyers Guide also classifies weight ranges for primal and sub primal cuts, fat trim, and portion cut weight tolerances.